AI Auto-Responses and Treating Others as Objects

There’s a particular use of AI that is becoming more common. Sure — students use it to write essays for them, businesspeople use it to brainstorm ideas, but, as is becoming more common, normal people are using it to communicate.

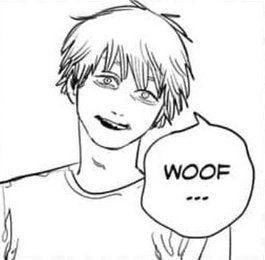

By this I mean that it is beginning to act as a mediator. I receive a text from a friend, and right above my keyboard Apple Intelligence is offering its best guess as to what I’ll say next. Or, closer to what I wish to discuss today, is a new feature of ‘Galaxy AI.’ I’ll let the picture speak for itself:

Rather than predict the next word, we can rid ourselves of the bother that is responding to a text altogether.

But that isn’t even my subject for this piece. I want to talk about Substack. The other day, I stumbled into a new blog. It seemed cool, and had content that was relevant to my interests. There happened to be a post I disagreed with so I left a comment. Now—I am not bragging here—I will at least say I put effort into that comment. I tried to explain why I disagreed and where I thought the writer had gone wrong.

I refreshed my notifications tab on a timer until I got one of those chillingly fulfilling ‘heart’ notifications. To my surprise, quickly following it, was a lengthy comment. I was excited! My first substack comment-section discussion.

Okay, it wasn’t a discussion. It was more of a head-pat. But that’s fine. I get it. I’m glad my contribution was appreciated and taken under consideration — I couldn’t ask for much more!

Though, it was worded a bit weird. I am sure you can see where this is going, but I have to say it anyways. I thought to myself, “No way. It can’t be. Right?” and put it into an AI checker. 100%.

I went through a few different stages of response before I settled where I am at now. My gut reaction was to think to myself “Wow, this is the state of the internet” and move on with my life. That’s at least what I wanted to do.

But it bugged me a bit. I started to worry that I had committed a Substack comment faux-pas. Maybe it isn’t a great idea, right after subscribing to a blog, to leave a critical comments. I suppose it does put the author in a hard position. Respond and defend their views but risk alienating me, or agree and risk seeming like a total grifter. I could imagine why someone would leave responding to those sorts of comments to AI.

But, this isn’t entirely right. They had another option. Instead of responding or grifting, they could have gotten annoyed at me for putting them in that position and ignored my message. I will argue it is this response that recognizes my humanity.

I want to nip a disagreeing chain of thought in the bud right here. There is a rejoinder to what I just said — it goes something like “ol, be pragmatic. If they ignored you, that would have put them in a bad position. You’re a new subscriber and they didn’t want you to feel like you were speaking into a void and unsubscribe.”

This is what seems to me most likely to have been going on in their head. They don’t want to be too divisive, and, at the same time, refrain from ignoring me outright. So, they defer to an AI.

That is not at all comforting. In fact, I feel much worse about that comment—the one that received an AI response—than I do about my other comments that have been ignored. I want to throw my hands up and say: “So my comment wasn’t even worth ignoring?!”

I want to step away from this particular example, in part because I do enjoy this writer’s content, and don’t want them to, in the event they read this blog, feel unduly called out or targeted. I am, after all, talking about a wider cultural phenomenon: our pushing the job of communicating onto AI rather than doing it ourselves.

My worry is that, while such a way of relating to others is always an option, to take it is to fail to relate to them in the special way that we are able to relate to other humans.

When we utilize auto-responders, our situation looks more like the situation of an excited dog and a busy owner. This owner knows that if he avoids the dog, doesn’t feed it, doesn’t at least pretend to care about it, it will become bothersome in various sorts of ways. So, he puts on a show. He works around and appeases the dog. He feeds him, rubs his belly, and gives him attention. But this is appeasement, and it is a lie. Our owner isn’t rubbing the dog’s belly with love, putting food on his plate because he wants him to eat and be healthy, but because our owner wants to get back to work.

Two things can, of course, be true. Our owner might well also want his dog to eat, and there may be some times when he wants to rub the dog’s belly for real—but, right now, he isn’t thinking about any of that. Right now, that isn’t his dog, it is an obstacle work—and obstacles are things to be planned for, worked around, and avoided where possible.

In the same way, when we use an autoresponder, our task is fundamentally one of appeasement. Like the dog, we treat the other person as something we need to deal with in order to do what we really care about, what really matters. In that sense, the perspective we take to them is not that different from the one the owner takes to the dog.

Here is a quote from the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, describing a paper by Peter Strawson. The paper is called Freedom and Resentment and it is hard and complicated and about free will. But it is also about blame and treating other people like humans, and, I think, about that perspective.

“Strawson’s aim in this paper is to dissolve the so-called problem of determinism and responsibility. He does this by drawing a contrast between two different perspectives we can take on the world: the ‘participant’ and ‘objective’ standpoints. These perspectives involve different explanations of other people’s actions. From the objective point of view, we see people as elements of the natural world, causally manipulated and manipulable in various ways. From the participant point of view, we see others as appropriate objects of ‘reactive attitudes’, attitudes such as gratitude, anger, sympathy and resentment, which presuppose the responsibility of other people. These two perspectives are opposed to one another, but both are legitimate.”

Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy

Imagine I am that dog owner. When I ‘work around’ my dog’s excitement, I take an objective perspective with respect to him. I treat him like an ‘element of the natural world’ and, thus, he figures into my thinking like all elements of the natural world do. I have my own interests, and will work around or utilize these things in ways to realize them. If I want to go to the beach and it is going to rain, I take an umbrella. I don’t, most of the time, get angry at the rain—treat it like another person, another agent. I take an objective stance towards it.

There is an important qualification due here. We don’t only take the objective point of view towards the rain. As I understand it, we take it towards other people too. Teachers often take it towards students (‘You can’t get mad at them, they’re just kids’), marketers or people trying to predict the behavior of others often take it with respect to the others (‘Given the data on human responses to the color red, this is probably how people will react to this ad’) and so on. Taking this perspective towards others doesn’t immediately mean we’re wronging them or treating them poorly.

That aside, though, this is also the perspective one takes when they pass a comment off to an AI to generate a response, or use an AI to avoid a conversation. When someone makes a decision of this sort, they forego distinctively human types of communication: disagreement, rebuffing, and so on, in favor of dealing with the comment or text in the way most amenable to their interests. To treat someone in this way is, like we said, it is to work around them; To treat them like a part of the world to be planned for, delegated away, and moved past, so one can focus on what really matters.

I hope to have drawn attention to the fact that when we use an AI to generate a response to another, whatever the context, we are taking up this perspective. To engage with another person in that way is to fail to view them in the distinctive way that we view persons; to take, towards them, a perspective normally reserved for inanimate objects or lesser animals. While, as times change and technology evolves, such a perspective may become necessary given our increased business and loftier goals, its ‘necessity’ marks our loss of the distinctive sort of lives we lead as humans faced with other humans.