Harmony as an Ideal and a Pathology

The Ideal Of Harmony

It is taken for granted that we ought to live Harmonious lives. Why shouldn’t we? The alternative is a life that is unharmonious, one that does not fit its pieces together well. Why should an unordered life be desirable?

In fact, Harmony exists often as an invisible standard that we, and others, hold ourselves to—often without knowing it.

It is quite common, after all, to imagine oneself as having a ‘core’ of sorts. An interest, or some set of them, that define who we are. This core is both inward and outward facing.

I, for example, talk about philosophy a lot. You might describe it as a ‘core’ interest of mine. Because of this, I try to bring my other interests into line, or, perhaps, under the heading of, my core. Appreciating the philosophical sides of movies and tv shows, seeking out philosophical activities and conversations. Others, too, collude with me on this: our conversations will often gravitate towards philosophy. If I mention an odd interest, something that does not clearly fit in, they might respond—without a hint of distaste—”Ah, that seems so out of character.”

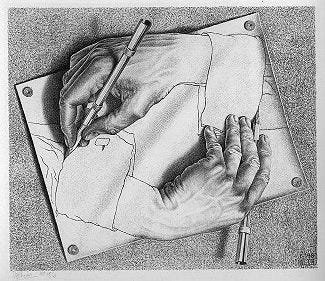

It is this idea of character, of remaining within a character, that is central to harmony. The thought goes something like this: “It is desirable that all of my interests fit together somehow. I am a ‘gym-bro’ or a ‘soft-girl,’ and what I do ought to be able to be brought under that heading.” I must, thus, ‘harmonize’ my character traits and interests; I must bring them all under a similar and shared heading.

A perhaps more tangible example of this might be the urge to ‘always be authentic.’ There is a sense that there is someone who we are, someone that exists beyond social interactions. And, we might find ourselves worrying, this person is often repressed or hidden by convention. We default to different vocabularies or topics of conversations around different people, for example. We’re more or less loud.

This, again, may begin to look or feel as a sort of failing. As a failure to be authentic, to be a consistently organized person. A person with different faces for different crowds might, thus, worry that they are internally disorganized or disunified. That they are not a single person, but many: divided. Thus, worries about authenticity can, at times, be worries about harmony—worries that we aren’t a single, unified, integrated person.

There are many more examples of our secret aspiration to harmony. We fear friends from different parts of our lives meeting; we live ‘secret lives,’ out of fear that if someone from a different part of our life becomes aware of an interest of ours, we will, in some unclear way, become less intelligible, and we decry ambivalence in our emotional life—preferring, rather, to feel one way or the other.

We chase an ideal: being unified, being a single, harmonious person, being one. Yet, it is certainly notable that when we ask ourselves what this is or, even, what is so desirable about it in the first place, we come up empty-handed.

Really. Why should we have ‘a character?’ Why can’t you be a ‘gym-bro’ and a ‘soft-girl’? What’s so wrong with that?

Things get even more complicated when we recognize that these are often not merely ideals, but things to be strived for. People strive to be entirely minimalist, to be authentic—the same person all the time. Even though this doesn’t sound like the worst thing in the world, it is not even clear what a good answer would look like. A reason to strive for authenticity? Hmm.

In this short section, I want to look at the writings of others. Specifically, the writing of Plato and then Jonathan Lear.

Plato On The Well Ordered Person

In The Republic, Plato, under the name of Socrates, embarks upon an awesome task. He wants to tell us what justice is. And, specifically in the context of Book IV, what it means for a city, for some political organization, to be just. Plato is not looking at a city for no reason. In fact, his reason is quite simple: a city is bigger than a person! And, according to him, “if we [try] to observe justice in some larger thing that [possesses] it, this [will] make it easier to observe in a single individual” (434d).

So Plato goes on, trying to say what a just city is. And he ultimately settles on what it is for a city to be just.

“Justice, I think, is exactly what we said must be established throughout the city when we were founding it—either that or some form of it. We stated, and often repeated, if you remember, that everyone must practice one of the occupations in the city for which he is naturally best suited…Then, it turns out that doing one’s own work, provided that it comes to be in a certain way—is justice” (433b).

Wonderful! Plato then applies this to the individual. A bit later, writing:

“And in truth, justice is, it seems, something of this sort. However it isn't concerned with someone's doing his own externally, but with what is inside him, with what is truly himself and his own. One who does not allow any part of himself to do the work of another part or allow the various classes within him to meddle with each other. He puts himself in order, is his own friend, and harmonizes the three parts of himself like three limiting notes in a musical scale—high low and middle. He binds together those parts in any others there may be in between, and from having been many things, he becomes entirely one, moderate and harmonious. Only then does he act. And when he does anything, whether acquiring wealth, taken care of his body, engaging in politics, or in private contracts—in all of these, he believes that the action is just and fine that preserves this inner harmony and helps achieve it, and calls it so, and regards as wisdom the knowledge that overseas such actions. And he believes that the action that destroys this harmony is unjust, and calls it so, and regards the belief that oversees it as ignorance (443c-e).

For Plato, existing as a harmony is, on the one hand, an activity. It is a person’s binding himself under his reason. In this sense, Plato’s picture of the harmonious person is not terribly different from our modern day one. In both, harmonizing is an activity, a binding.

Yet, at the same time, Plato is (somehow!) more liberal. He does not require that a just person repress his other parts (things like desire or anger) in the name of reason. His harmonious person is not necessarily a boring one, a person whose character can be defined in a single word.

Specifically, a person, for Plato, is just and well-ordered as long as his basic parts do not overlap, as long as they do not step on each other’s territory. Thus, while giving into temptation or greed may be an example of this—being ruled by desire, for example—everything else goes. One can have a diverse set of interests, a variety of faces, as long as they are not in conflict in some deeper way. As long as she is not in what Plato calls a state of “civil war.”

As long as a person is ruled by reason, as long as her other parts—her anger and appetites—stick to their own territory, then she is harmonious. For Plato, at least.

Jonathan Lear on Integrating the Unconscious

In an essay titled Integrating the Non-Rational Soul, Lear explores Aristotle’s understanding of the soul, of virtue and rationality.

Now you might find yourself wondering what virtue and rationality have to do with our discussion. For Lear and Aristotle, these terms in this context do not mean what we might normally expect them to. It is not about reasoning from premise to conclusion or being a good, virtuous Christian, but rather, having a certain special sort of internal organization. This is similar to how Plato’s discussion of Justice ended up being a discussion of internal harmony.

Lear begins, writing:

“For the virtuous person—in this case, Aristotle mentiosnm the temperate and courageous person—Aristotle gives us two criteria: first, the non-rational soul is better able and more willing to listen…to reason; second, with respect to all things, the nonrational soul speaks with the same voice…as reason. That is, the excellence of the nonrational part of the soul consists in communicating—listening to and speaking with reason” (30).

He ends by discussing a conversation he had with one of his patients, his analysand, Mr. B. I’m going to quote it at length.

“He comes to a session and begins to report a dream he had the night before.

'I’m watching cars that drive through red lights. They keep on going through. I have a series of reactions. They’re getting away with something. They shouldn’t be doing that. I feel angry; why didn’t I do that? Could I get away with it? What stands out is: they got away with it. There’s no accident, no police siren.’

At first he does not associate to the dream; he talks instead about problems at work…and then Mr. B said:

‘Maybe that’s why I’m having dreams, seeing other cars racing through red lights. I’m not doing that. It makes me mad. I’m the one who stops for the green light. I even stop for the yellow light. Other people don’t and they even get away with it.’

I was struck by his slip of the tongue; and I had a sense that Mr. B had not noticed it. This is a moment in which the unconscious breaks through…and speaks with its own voice. I said:

‘You said you’re the one who stops for the green light.’

Mr. B responded:

‘No! I didnt know I said that…’” (39-41).

Analysis pressed on, and, eventually, Mr. B said:

“‘Ah, what would it be for me to just let myself go through a green light!?’ He sighed, and the muscles in his hands—which he had been rubbing together vigorously—relaxed. I sensed an overall relaxation in his body. It was as though, in body-and-mind, Mr. B was coming to some sort of summing up” (42).

Over the course of this exchange, something good happened to Mr. B. I submit, and I think with Lear, that for a moment, in the safety of the analytic situation, his conscious and unconscious mind spoke in the same voice. He was a singular, unified person.

What this case illustrates, I think quite beautifully, is that for a patient like Mr. B, harmony has very little to do with his projects, with whether he is a ‘gym-bro’ through and through. In fact, Lear spends no time in the piece giving any attention to whether Mr. B’s projects cohere together, whether they make sense under the heading of some more general character.

What it is for Mr. B to exist harmoniously, rather, is something much more complex. It is what he experienced at the end of their session: when he finally expressed his wish and, simultaneously, freed himself from his self-imposed chains. As Lear says, “conscious and unconscious are in effective communication with each other” (43). When he relaxed, he was no longer speaking as a prisoner, as someone with a cruel unconscious mind holding him back. He was, instead, speaking in one voice: speaking for both his conscious, his rational mind, and his unconscious one. So when he wished he would release himself from his chains, it was not mere lip service. It also just was him releasing himself from his chains.

This was possible because he experienced a moment of unity, of harmony. And it is worth, I think, dwelling for a moment on how different this harmony is from the ideal we started with. Mr. B is not freeing himself in the name of some core interest or anything like that. Harmony, for him, is a mode of communication, of internal cooperation.

I have just thrown a ton of philosophy at you, so it will be useful to, for a moment, take stock. Plato presented a picture of the well-ordered soul, of the just person. This picture required that the parts relate to each other in a certain way, but not that they be all of a kind, or anything like that. Lear and Aristotle, of course, give quite a different picture — but, at least, this feature is shared: in their case, ‘effective communication’ is prized.

Contrast these pictures that view harmony as a sort of ‘internal organization’ with the ones we began with: with the idea of having a ‘set’ character, of being a gym-bro or a soft-girl, of being a ‘philosopher,’ and so on. Not only are Plato and Lear’s pictures more complex, but they also allow for a more complex expression of personality. They do not much care whether we work out and do art and enjoy dark-academia-styled decoration.

Further, when viewed from the perspective of Plato or Lear, we might begin to worry that our initial understanding of harmony is not merely wrong, not merely a misunderstanding, but itself an instance of disharmony, of disunity.

Take the examples of being a ‘gym-bro’ or ‘soft-girl’. To force oneself into such roles is to confine one’s emotions, aspirations, and desires to those, and only those, acceptable for a ‘gym-bro’ or ‘soft-girl.’ Of course, it is unrealistic that these will be our only emotions, aspirations, and desires—so, for such a person, the feelings that arise which are ‘out of character’ will be set aside, ignored, or repressed. At this point, such a person begins to resemble someone quite internally disharmonious: constantly at civil war, and constantly, like Mr. B, denying themselves. It is a picture of a person who ignores the voice of their unconscious.

In this light, what is at first glance an aspiration to harmony is, from a better vantage point, a desire for mastery. It is an attempt to control, through the act of ‘naming,’ of casting into a role, our desires and emotions. We fit ourselves into categories, into characters, in hopes that we will become characters, in hopes that we will be predictable, and that we will be able to avoid the complex beings we are.