The Role of the Other and Interpretation

For reference, I will be building themes and ideas introduced in this piece. Reading it is not necessary, but I take the two to compliment each other quite nicely.

Here are two events that are common enough to warrant philosophical investigation.

I am spending time with a friend. After talking for a while, we shift onto a new topic. Something has been bothering me recently. I am torn between two different life paths: becoming a writer and becoming a teacher. My friend then shares a story. He was once in a similar position, he tells me, and for him what was so challenging wasn’t just the two options, but the two lives they represented.

After hearing my friend’s story, the conflict suddenly begins to feel much more palpable. It is as if, prior to talking, my feeling it was akin to a mere groping. It was vague, shapeless, and inarticulable. And not just inarticulable to others, but to myself: I was not yet able to say, “I am torn between two different ways of life,” but only that I was conflicted between two options.

Now, with my friend’s contribution, my experience is fuller in quite an interesting way. I will say more about this later, but tease you a bit now. It is not that I know more about the emotion. There was not anything more, prior to our conversation, for me to have known. Of course, there could have been—maybe I didn’t know what I was feeling; but for me to react to my friend in such a way, this need not be the case. I do not need to have been unsure of what I was feeling to experience this clarity, or to have been wrong. I could have been quite sure, and quite right. I was feeling conflicted.

How amazing, then, that now, I am more than conflicted; I am torn, and it is as if I always was.

But more on that later; I promised you another example. This phenomenon is not confined to my emotions. Consider another case. I am complaining to my friend, Ms. X, about the behavior of another, Mr. Y. I tell Ms. X about all the different ways Mr. Y has wronged me: how he always shows up late, how he takes forever to respond to my texts (even when I am quite clear that they are urgent!), and so on. “How could someone be such a bad friend!?” I proclaim, ending my tirade with a rhetorical question.

Ms. X, upon hearing all this, thinks for a moment. Then she destroys my world. “He doesn’t much like you at all, does he?”

Once more, everything has changed. It is as if all the behaviors have suddenly been tied together nicely, like they have fit into place. Ms. X has supplied me with the blueprint to finally make sense of what has been going on in front of me for so long.

Now, I don’t mean to imply that this isn’t an emotional moment. It is quite likely that upon viewing Mr. Y in this new light, I am able to feel a variety of new things: my frustration can change to anger, or perhaps indifference. Maybe I am less confused.

But—and this is important—the substantive thing that has been gained is not a new perspective on my emotion but on the relationship, on my situation. I am suddenly thrust into seeing it in an entirely new light. Once more, it is as if it has been like this the whole time.

“How could I have missed it?” I say, dumbfounded. “He hates me.”

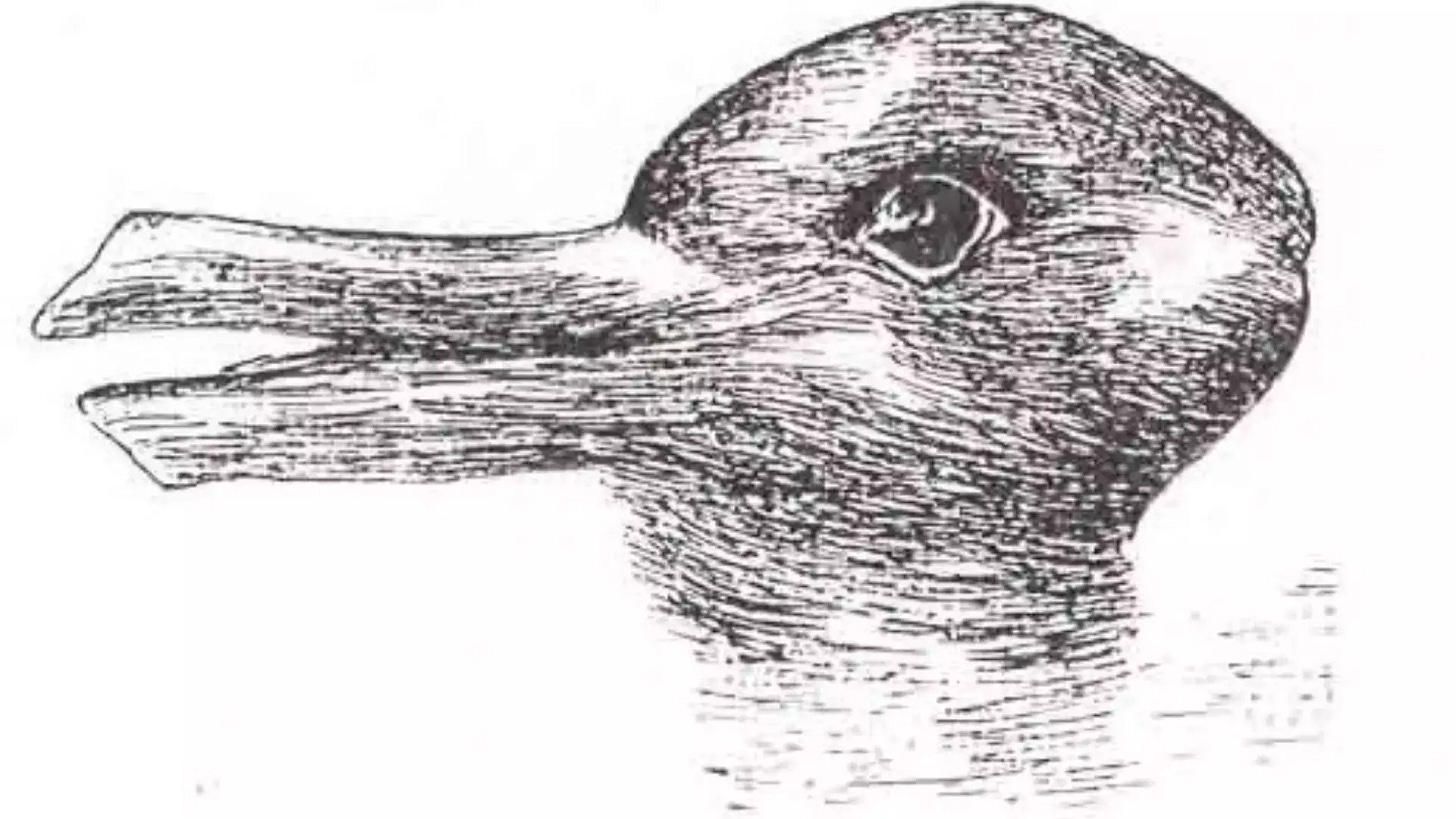

Is this a picture of a rabbit or a picture of a duck? Both are right answers. Depending on how you look at it, you will see a duck (the protrusion on the left is a beak) or a rabbit (no! those are clearly ears).

Unlike the previous two examples, philosophers have thought an awful lot about this image. We are able to appreciate different facets of it. In other words, we are able to see it as an image of a duck at some times and, other times, an image of a rabbit. It is not as if our seeing changes it somehow; rather, it is as if we are interpreting the same picture in two different ways. Seeing the same set of facts as two different things (For more reading on this, consider starting here or here).

This suggests an easy answer to the question just raised. Maybe our conflict, or the experience with Ms. X and Mr. Y, is a case of the rabbit-duck illusion! After all, the three cases are intriguingly similar. Like the image, the things we come to know are new interpretations of the same facts. My torn-ness is certainly one way of ‘seeing’ the conflict that was already present, and Mr. Y’s not being a friend is one way of ‘seeing’ his behavior.

This will not do, sadly. First, it is worth noting that in the case of the rabbit-duck, we can go back and forth. Look, it’s a rabbit! Look, it’s a duck! And so on. We could do that all day until we’re blue in the face—but, notably, we can’t do that in the case of our conflict or Mr. Y. These interpretations, ways of seeing our emotions or the actions of another, have a sort of staying power that no duck-seeing or rabbit-seeing could. They aren’t just possible ways of seeing things we take up on a whim, they are new ways of seeing things we embrace as correct.

Of course, this is not always true of rabbitduck like examples. You are seeing the various marks on this page as words (like the second article emphasizes!) with meanings. I would be asking something very weird of you, though, if I said: “Okay, now just like you switched back to seeing it a as a duck, can you switch back to seeing these words as squiggles?” So maybe there are some rabbitduck cases that we can’t reverse.

This aside, there is a deeper way in which the cases—the case of the rabbitduck on one side, and the cases we began with on the other—differ. In the case of the rabbitduck, only one person is necessary. You, reader, began this section by trying the experiment for youself. And, if you’re still reading, I assume it worked.

At best, in the case of the duckrabbit, another person draws your attention to a way of seeing the image that you hadn’t seen before. Maybe that is the role I played, for you, when I talked about the beak and the ears. But you don’t need me. You can find the beak yourself, and you can find the ears yourself. It is at least conceivable that you look at the image for a while and think, in the quiet of your mind, “Woah, this looks like a duck and a rabbit depending on how I see it. Cool!”

This is not so when it comes to our earlier experience of conflict, or imagined scenario with Ms. X and Mr. Y. In both cases, the trusted friend plays an essential role. Without them, we would be left where we began. We would be left feeling ‘conflicted,’ or without an understanding of why on earth Mr. Y could be doing all those things. More on this in a couple paragraphs.

When a friend tells me a story, when he tells me of his own experience with a similar emotion, he tells me his name for that emotion. He tells me the description under which he felt it. When Ms. X tells us how she sees all of Mr. Y’s behavior fitting together, she tells us the description under which she sees it. In both cases, we are given a new interpretation of something we were already well acquainted with. It is this interpretation that plays this special role for us, that upends our mental lives.

So, we can restate our initial question. What is it about the interpretations that other people give us—and it is essential that they are other people—of our own situations that allow us these epiphanies?

First, a word of caution. This is not a question of access. It is not that our friends are simply pointing us in the direction of a new fact, or a new interpretation. After all, in the example of conflict, I may very well say something like the interpretation I ultimately arrive at in passing. As I nervously pace about the house lamenting my condition, imagine, I might punch the air and think to myself, “Damn! I hate to be in such a position; to have to choose between two appealing lives.” Yet, in a case like that, such an interpretation will ultimately mean very little for me. I will forget about it, push it aside, and continue going down the path I was on: I am in conflict between writing and teaching. What to do?

Now, I don’t mean to say here that it is impossible for me to interpret or grow with respect to my own emotions. This is very possible! I realize that I don’t love her, that this party is not for me, and that I don’t quite like this movie. Such realizations are part and parcel of healthy mental lives.

Yet, in the two cases we began with, such a possibility was not open to me. In these cases, the revelations of the other are able to make such a difference for us exactly because we are not in a position to make that difference ourselves. Our interpretations, for whatever reason, fall flat. We might pose their possibility to ourselves, ‘Perhaps Mr. Y simply does not want to spend time with me,’ but the possibility remains just that—a mere possibility, an option we are entertaining. Yet, when it comes from the mouth of another, it suddenly falls into place.

Believe it or not, this is the beginning of an answer. We are able to formulate our question one last time, at least for now. We are interested specifically in the cases wherein it is only the interpretation of another: their interpretation of our emotions, or of our situation, that can make a difference for us. Without them, we are left with a flat affect. We raise the possibility that we are torn between different lives, or that he doesn’t quite like us, but it never counts for us in a deeper way.

This is our problem, but it is also a statement of why it matters that another person gives the interpretation—it is a statement of what they do for us. So, finally, we must ask: Why aren’t we in a position to make a difference? Why don’t our interpretations count in this deeper way?

Let’s return to the cases we began with. In the first, I am torn between two jobs and, through the interpretation of a plan, come to see that I am in fact torn between two different lives. In the second, I am unable to make sense of the behavior of Mr. Y until Ms. X gives her interpretation of it. Suddenly, it all clicks into place: he never much liked me to begin with.

Both times, a trusted person pulls the disparate pieces of our lives together for us. They pull together our emotional experience with our hopes and dreams, and, in so doing, allow us to see what we at first could not. They pull together the various senses in which a friend has failed us and finally allow us to see how he truly feels. They pull together our various experiences of conflict and our actual conflicting desires—our dream of writing and our urge to teach.

This, by the way, is why we can’t switch in and out of these interpretations like we can with the duckrabbit. To do it in these cases, we would need to pull ourselves apart.

So, our friends pull us together in our time of need and, once we are whole again we gain the ability to see ourselves and others for what we and they are. That’s what their interpretations do. They allow us to see the whole picture of ourselves: we are no longer confined to the perspective of separate pieces, but can view ourselves as a whole.

This is why it is important that they are their interpretations, that they come from another. After all, how could we put ourselves back together? We’re the very things that have fallen apart.

We are in pieces, and they put us back together by helping us see the truth about ourselves—they pull the different parts of our lives emotions and worlds together. Only they can do that. But once we are back together, we can see the truth about ourselves on our own. We’re back together, after all.

I have not answered all the questions raised here. What does it mean to be torn, to be in pieces? Why is it that having a realization like this, it is as if I have always known? Why can’t I do this work on my own?

last paragraph was such a beautiful way to conclude it